If you’re pregnant, you may have already had an obstetrician mention the idea of a Planned Birth (PB), induction or scheduled caesarean in your 39th week.

One of the studies your OB might use to support this recommendation is a new analysis from Queensland.

At first glance, it seems to suggest that PB at 39–39+6 weeks can improve outcomes compared with Expectant Management (EM), waiting beyond 40 weeks for labour to start naturally.

But when you read past the headlines, the story becomes far more complex. This paper leaves some important questions unanswered, and, perhaps without meaning to, highlights some of the very real risks of intervening before labour starts on its own.

The headline finding — and the first red flag

The authors looked at outcomes for over 1.2 million Queensland births between 2001 and 2020. They ended up comparing 472,520 low-risk women who either under went who either underwent planned birth (by induction of labour or scheduled caesarean sections) or who had expectant management:

-

PB at 39+0 to 39+6 weeks (induction or scheduled caesarean)

-

EM (pregnancy continuing beyond 40 weeks)

They found that PB was linked to slightly fewer caesarean sections, adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes and perinatal deaths. But, and this is a big one, for first-time mums, induction at 39 weeks was associated with a higher chance of caesarean compared to EM.

“For nulliparous women, induction of labour at 39+0–39+6 weeks was associated with higher odds of caesarean section than expectant management.”

Despite this, the authors go on to claim:

“Our findings that women who underwent induction consistent with the ARRIVE trial of labour had lower rates of caesarean birth”

Which is stretching the truth because the ARRIVE trial only looked first-time mums, actually found the opposite.

As a side note:

The ARRIVE trial has had its fair share of critiques, and for good reason.

- Henci Goer has written an excellent breakdown of ARRIVE’s flaws, including the way results were presented and the highly medicalised setting. Read her analysis here.

- Dr Sarah Buckley highlights the hormonal, physiological, and emotional implications of induction and early birth in her critique here.

- And I’ve written my own piece for doulas, unpacking the implications of ARRIVE and why it doesn’t mean “every woman should be induced at 39 weeks” — you can read that here.

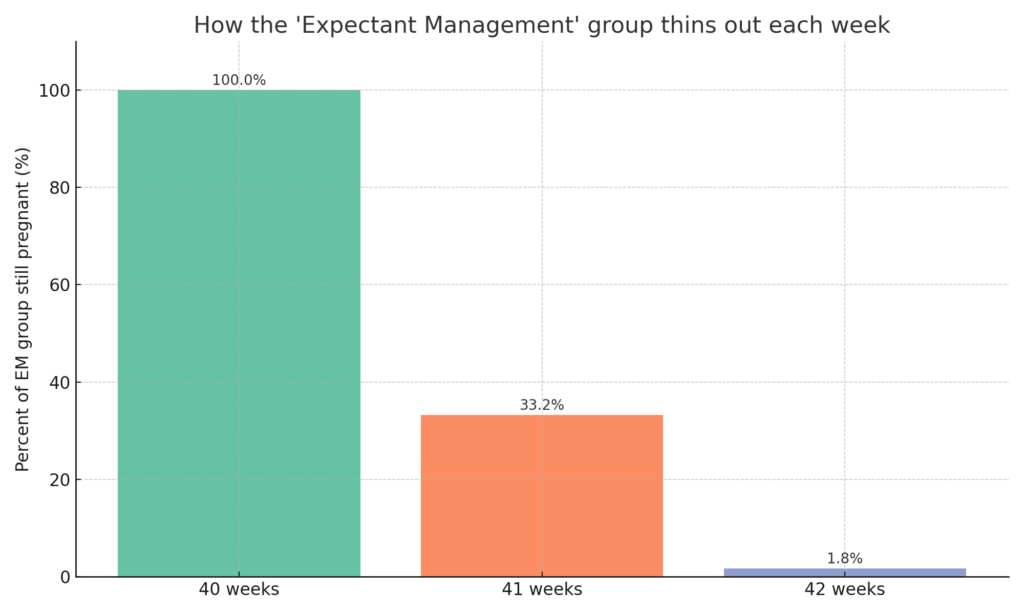

The hidden problem with the EM group

Another key issue is that the study’s “expectant management” group, those who gave birth at 40 weeks or later, almost certainly included many women who were induced anyway, just a few days after 39 weeks. Queensland’s own perinatal statistics show that more than half of women still pregnant beyond 41 weeks are induced, and even by 40 weeks, induction rates are already climbing steeply.

This means the study might have been comparing induction at 39 weeks with induction at 40–41 weeks, rather than induction with spontaneous labour.

What’s the real average length of pregnancy?

We’re losing sight of the natural timeline for pregnancy because induction rates are climbing every year. A 1990 study of uncomplicated, spontaneous singleton pregnancies found:

-

Median gestation for first-time mothers = 288 days (41+1 weeks)

-

Median gestation for mothers with previous births = 283 days (40+3 weeks)(Mittendorf et al., 1990)

Yet in this Queensland data, EM babies were born at a median of 40+2 days.

Why the outcomes in EM might not be what they seem

Another problem is that while the authors do break down the mode of birth in the EM group ( 37.6% induction, 2.1% planned caesarean) they don’t report which mode of birth within the EM group was linked to the poorer outcomes they observed.

Without separating the results for spontaneous labour, induction, and planned caesarean in the EM group, we can’t tell whether the risks were higher because of the inductions, the planned caesareans, or some combination of both.

This is a critical gap because inductions are stressful for babies. Studies have shown that babies born after induction can have higher cord blood cortisol and catecholamine levels compared to those born after spontaneous labour, indicating increased physiological stress during birth. These situations may also increase the chance of interventions like emergency caesarean, which in turn can influence short-term newborn outcomes.

Lumping all modes of birth together makes the EM group’s results look less favourable, but may not reflect the outcomes of truly spontaneous, physiological labours.

Relative Risk vs Absolute Risk — why the way numbers are presented matters

When research findings are presented to the public, or even to health professionals, they are often shown as relative risk. This means the difference between the two groups is expressed as a percentage change rather than the actual numbers.

This paper’s abstract uses relative risk and percentages, but if you read on, you will find the absolute numbers and numbers needed to treat (NNT). This is why it is always important to read beyond the abstract

The problem? Relative risk can make a small difference look much bigger.

Here’s an example from this study (taken from figure 2) :

-

In the EM group, the rate of perinatal death was 0.25 per 1,000 births.

-

In the PB group at 39 weeks, the rate was 0.69 per 1,000 births.

The abstract states the relative risk :

“Planned birth was associated with 52% lower odds of perinatal mortality”

That sounds huge. But if you look at the absolute risk, the difference is actually 0.44 per 1,000 births.

The paper does state the NNT and concludes that you would need to plan around 2278 births at 39 weeks to potentially prevent one death.

Why this matters:

-

Absolute risk tells you the real-world difference — the actual chance that an individual will benefit.

-

Relative risk can make benefits look much larger than they truly are, which can sway decision-making without showing the full picture.

For parents, this means it’s worth asking:

-

What is the absolute risk difference?

-

How many women and babies would need to have this intervention for one baby to benefit?

-

Is this worth putting all those mothers and babies who don’t need the intervention at risk of the intervention itself?

In this study, some of the benefits of PB look statistically significant in relative terms, but when you convert them to absolute risk, the improvements are very small, especially for low-risk women.

Severe Perineal trauma: putting the numbers into perspective

This one always makes women take note, and severe perineal trauma is something to be avoided.

The study also looked at rates of severe perineal trauma (third- and fourth-degree tears). These were:

-

EM: 24 per 1000 births (2.4%)

-

PB: 15 per 1000 births (1.5%)

That’s an absolute difference of 9 women per 1000 births — or to put it another way, you’d need to offer PB to around 111 women to potentially prevent one case of severe perineal trauma (the “Number Needed to Treat” or NNT).

If we looked only at the relative risk, this would be presented as a 37.5% reduction, which sounds much more dramatic. But absolute risk tells us the real-world difference is small for most women. This is why reading beyond the headline numbers matters so much when weighing up the pros and cons of induction or caesarean at 39 weeks.

Obviously, a caesarean will prevent severe perineal trauma but does this outweigh the risks of a caesarean section? And there are other less dramatic ways of lowering your risk of severe perineal trauma.

Dr Rachel Reed is an excellent resource in this area

Has this paper actually highlighted the risks of induction?

Another of the study’s limitations is that the study groups inductions and booked caesareans together under PB. In reality, they carry different short- and long-term risks.

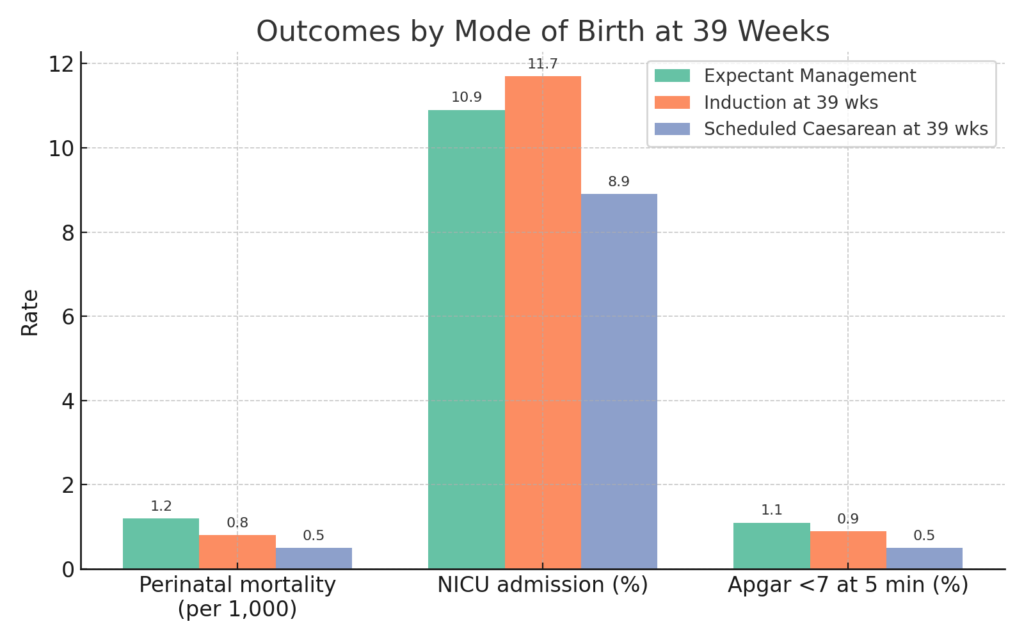

When you dig deeper into the results, the outcomes for these two types of PB were not the same:

-

Scheduled caesarean at 39 weeks had the lowest rates of perinatal mortality, NICU admission, and low Apgar scores.

-

Induction at 39 weeks had outcomes that were closer to, and sometimes worse than, those seen with Expectant Management (EM).

.

Figure: Birth outcomes for expectant management (EM), induction at 39 weeks, and scheduled caesarean at 39 weeks.

Notice: NICU admission was higher after induction at 39 weeks than with EM.

While the authors focus on the potential benefits of Planned Birth (PB) at 39 weeks, the data could also be read as a warning about the risks of induction.

A 2021 16-year study from NSW by Professor Hannah Dahlen and colleagues looked at over 1.2 million births and found that, for low-risk women, induction was linked to:

-

More interventions – More epidurals, more instrumental births, more caesareans, especially for first-time mums.

-

More complications – Higher rates of postpartum haemorrhage, even after adjusting for other factors.

-

More issues for babies – More neonatal resuscitation and NICU admissions, despite being term.

-

Lower breastfeeding rates – Fewer babies were exclusively breastfed on discharge.

-

No survival benefit – Perinatal death rates were no lower for low-risk pregnancies.

All this raises the question: Are these “better PB outcomes” really about timing… or are they showing us that induction can be a tougher, more stressful way to be born?

And that makes sense when you think about it. Induction short-circuits the hormonal cascade of labour — the very process that prepares both mother and baby for birth. Babies find induction stressful, especially smaller late-preterm babies.

So, instead of simply concluding that “PB at 39 to 39+6 weeks is safer,” this paper may be inadvertently showing us the risks of induction.

If that’s the case, then the safest strategy might not be to induce earlier, but to support more women to go into labour spontaneously wherever possible, and reserve induction for clear, evidence-based medical reasons.

Is planned caesarean at 39 weeks the answer?

It might be tempting to think a scheduled caesarean at 39+0–39+6 weeks is the “safer” option for low-risk women, since it appears to reduce short-term risks like perinatal death. But this study, and broader obstetric evidence, highlight that caesareans carry significant long-term implications.

In Western Australia, King Edward Memorial Hospital Consultant Obstetrician and Gynaecologist Dr Mathias Epee is warning of the rise in cases of placental accreta. A dangerous condition where the placenta implants too deeply into the uterine wall.

A recent news post highlighted that the Placenta Accreta Service typically treats seven to 10 women a year with the condition; however, this is starting to rise, and the hospital recorded 24 cases last year, highlighting why avoiding unnecessary caesareans matters, even when things seem safe in the short term.

“We know that it’s a worldwide problem that is significantly linked to the increase of caesarean sections in the community,” said Dr Epee.

So while a caesarean at 39 weeks may seem protective in the moment, it may trade short-term gains for higher future risks. From this perspective, it can be argued that it is safer to wait for spontaneous labour in low-risk pregnancies whenever feasible.

The missing conversation about long-term impacts

The authors do not address:

-

Breastfeeding: Evidence shows planned birth before 40 or 41 weeks can affect early feeding and milk supply.

-

Cognitive development: Every Week Counts highlights that critical brain growth continues right through 40 and 41 weeks. Babies born by earlier planned birth may face differences in school readiness and cognitive scores.

-

Caesarean-related risks in future pregnancies: A caesarean now increases risks such as stillbirth in subsequent pregnancies, and life-threatening complications like placenta accreta.

Every Week Counts has excellent resources explaining why each week matters for brain and organ development.

“Allowing development to 40 weeks gives the brain opportunity to reach its full developmental potential” everyweekcounts.com.au

Early term is not the same as full term — and this study reinforces it

I want to finish on something that can be seen as a positive from this study.

And that is that it highlights the need to shift in how we define “term”. Many obstetric guidelines still refer to term as 37 to 42 weeks, but the data here — and from numerous other studies — makes it clear that birth at 37+0 to 38+6 weeks carries higher risks.

“Regardless of mode of birth, infants born at early term gestations (37+0–38+6 weeks) are at higher risk of complications, both in the short term — such as respiratory complications, admission to the neonatal intensive care unit, hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy, and seizures — and in the longer term, including poorer school performance, behavioural problems, and cerebral palsy.”

This study’s authors note these risks, strengthening the argument that we should redefine term to mean 39 to 42 weeks, and avoid non-essential births before 39 weeks unless there is a clear medical reason.

Final thoughts

This Queensland study offers plenty of data, but also plenty of unanswered questions. For expectant parents, the key takeaway is that Planned Birth (PB) at 39–39+6 weeks is not universally “safer” than Expectant Management (EM) after 40 weeks, especially for first-time mums, where PB was linked to higher emergency caesarean rates.

It’s also a reminder of why we must read beyond the abstract. Headline figures often use relative risk, which can make benefits look bigger than they are. But when we look at absolute risk and calculate the numbers needed to treat (NNT), the differences can be much smaller, and sometimes, the potential downsides outweigh the gains.

The decision between PB and EM will always depend on your individual circumstances, health history, and preferences. That’s why it’s essential to have honest, nuanced discussions with your care provider, ones that weigh all the short- and long-term risks and benefits, not just those that fit neatly into a guideline.

And while the data from this study is valuable, it’s just one piece of the puzzle. Different studies in different populations may find different results—so pinning your decision on one set of statistics is rarely the full story.

In other words, birth timing matters. But what matters even more is making sure the timing is right for you and your baby, not just for a calendar, a hospital policy, or a statistical trend.

References

Crawford K, Carlo WA, Odibo A, Papageorghiou A, Tarnow-Mordi W, Kumar S. (2025). Perinatal mortality and other severe adverse outcomes following planned birth at 39 weeks versus expectant management in low-risk women: a population-based cohort study. TeClinicalMedicine, 80, 103076.

Dahlen, H. G., Thornton, C., Kramer, M. S., Foureur, M. J., & Hutton, E. K. (2021). The association between induction of labour at term and neonatal and maternal outcomes for low-risk women: A linked data population-based cohort study. BMJ Open, 11(6),

Mittendorf R, Williams MA, Berkey CS, Cotter PF. Length of uncomplicated human gestation. N Engl J Med. 1990;322(10):588–592.